How to Be a Graphic Designer, Without a Soul

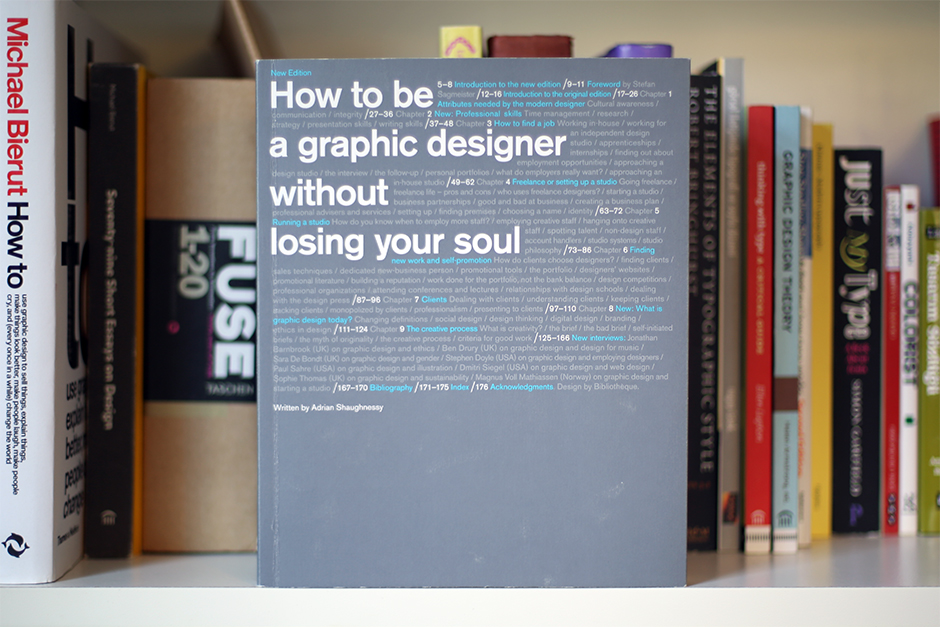

Review of How to Be a Graphic Designer, Without Losing Your Soul by Adrian Shaughnessy

I admit, I was a bit worried about the “without losing your soul” in the title of the book before starting, but Adrian Shaughnessy turned out not to be nearly as romantic as I expected; he even argues that self-initiated projects (“personal projects”) usually are not a good way to promote oneself and get new clients – something that doesn’t resonate well with the title, and something I don’t agree with even though I don’t believe in souls.

Interestingly, there are a few paragraphs where Shaughnessy is really soul-romantic at the beginning and they sounded so wrong to me that I even thought of dropping the book. I’m glad I continued because the rest was a gem, full of discussions and ideas that I’ve been thinking and talking about for years. The writing is conversational and humorous, and he generously exhibits his talent for making fun of himself – an important threshold for tasteful intelligence in my book. Maybe for these reasons, those paragraphs in the beginning kept disturbing my perception of the book.

That line of thought which threw me off starts with the construction of this dichotomy:

On the one hand, we have those who believe that graphic design is a problem-solving, business tool and that designers should suppress their desire for personal expression to ensure maximizing the effectiveness of the content. While on the other hand, we have those who believe that although design undoubtedly has a problem-solving function, it also has a cultural and aesthetic dimension, and its effectiveness is enhanced, and not diminished, by personal expression.

Even though Shaughnessy stresses the importance of an objective discourse in client relationships throughout the book, he’s taking a pretty strong position on the side of subjectivity in the design process:

In practice, this means that we use fonts, colours, layouts and imagery because of an inner aesthetic conviction – and when you think about it, it would be an odd designer who used elements that he or she didn’t like. (…) And here’s where the conundrum kicks in: we have to learn to present these ‘inner convictions’, these ‘intuitions’ as rational and objective. (…) Few clients will accept the argument ‘I’ve done it like this because I like it’, yet this is often what we’ve done.

For these ideas, he is getting support from Michael Bierut’s ‘On (Design) Bullshit’ – one of the few writings of him that I don’t like, for the reasons that Rick Poynor has articulated in the comments section. (This rhetoric question by Poynor is a strong counter-argument by itself: If it all comes down to subjective preference, then maybe we don’t need design education?) Shaughnessy is mixing things further up by arguing that every designer is in fact self-expressive, and that not doing everything clients say and standing up to them is also the result of this personal, emotional relationship with the work:

Let me put it another way: I don’t think I’ve ever met a designer who didn’t have the instinct for self-expression. You can see it in the universal reluctance to have ideas rejected, tampered with or watered down. There’s a mule-like instinct in nearly every designer – even the most accommodating and service-minded – that bristles at the command ‘Oh, can you change that’ and the ‘Just do it like this’ attitude so frequently adopted by design’s paymasters – the clients. It’s an instinct, inherent in all designers, that says: a little bit of my soul has gone into this and it is not going to be removed without a fight.

What about designers who acknowledge the cultural/aesthetic dimensions but still do it in a more objective fashion and not via personal expression? And what about designers who spend great efforts to protect their carefully constructed concepts/systems from clients’ whimsical demands, not because these designs are imbued with their souls, but because they are guided by design thinking and principles that the client isn’t aware of? What about the designer who sticks to her decision of using that red color, not because she loves it, but because it’s objectively a right thing to do according to the brief? (And yes, she can even hate that color personally, and still use it in a design, because she’s not designing for herself – oddly, this is an “odd designer” for Shaughnessy.)

And why assume that every designer by default has a desire for personal expression to suppress anyway? As I hinted at above, Shaughnessy’s argument about observing designers defend their work against paymasters is defective. To put it more broadly, isn’t it weird to think that something has to be personal/emotional in order to be worth defending in a professional relationship? Where does this thinking leave other professions? Do we expect people with non-self-expressive jobs not to give a damn about their work? Should engineers not be bothered when their calculations are tampered with?

Okay, got it, the author’s defend-the-work argument is a misfire, you might say, but design resembles art in that it offers elbow room for creative moves. And surely all artists have the desire for personal expression? This may be the source of Shaughnessy’s confusion, but even before considering listing the differences between design and art, I would argue that assuming every artist has that desire is also a cliché; many groundbreaking artists don’t operate on personal expression or inner aesthetic conviction but on “cold” rational thinking and external references. The much loved and respected self-expressive troubled artist represents in fact one of the recent (19th and 20th century) highlights in terms of art-making, and didn’t survive the 20th century according to many.

The oversimplistic dichotomy of service-minded designers who do everything the client says by suppressing their own desires and self-expressive designers who stand up for their work is so inaccurate that it stands out like a sore thumb in this otherwise great (and non-romantic) book. Many service-minded designers respect the service they provide so much that they don’t let the client ruin it. The tendency to put personal expression on a pedestal, to assume every creative person has the desire for it, and to define it as a requisite for respectable and meaningful design (and art) work needs explanation.

Maybe Shaughnessy’s conviction is mirrored in the case of believers who argue that atheists are in fact people who have faith deep down but deny or suppress it: “I have this belief/desire/feeling and I can’t imagine not having it so everybody must have it; and those who don’t reveal it are lying to us or to themselves”. Needless to say, this is a lack of vision – seeing everybody as modified versions of you at best. Believe it or not, people can really, fundamentally be different than yourself. You don’t have to model them in your own image.

I’m afraid that assuming every – genuinely! – creative act comes from the desires/mechanisms of personal expression and intuition also has to do with that archaic, romantic, almost magical outlook on creativity, safely embedded in the minds of the majority. Like so many other “mysteries”, people avoid objective and deterministic explanations and prefer to leave it at that: a mystery. How does this person make these interesting things? She is creative; that is just how she is (it’s something personal, or intuitive) – and that is the end of the explanation for many of us, as tautological as it gets. I believe that, as much as creativity can involve unconscious processes, it can be analyzed and synthesized in an objective, rational, down-to-earth fashion (some of my attempts are here, here, here) and that we should revise our lazy romantic conceptions about the role of subjectivity and personal expression. They don’t have to be involved in every creative act; and even when they are present, they can be analyzed, understood, and replicated – maybe with a lot of effort, but without any magic dust. Within this framework, we can have a more fruitful discourse of creativity/design/art without vague conversation enders, and we won’t be scaring young designers and artists by giving them “a feeling that they lack an important gift possessed by some others, a feeling which inhibits creative effort and increases dependence upon authority,” in Donald Campbell’s words.

The “inner aesthetic conviction” works in design because it’s a highly trained unconscious mechanism of selection installed in designer brains, based on education, experience, and exposure. Considering these three sources, the emergence and the workings of this mechanism aren’t all that mysterious, and “because I like it” coming from a designer always means more than a regular “personal” liking: whether she is aware or not at all times, it has reasons that can be uncovered and talked about from a design perspective to a great extent. Many designers prefer to externalize and pinpoint those reasons – think out loud, you might say – right from the beginning of the design process. (This is especially useful when there are multiple designers working together.) The uncovering of these reasons is also required in order to have meaningful and productive discussions in client meetings, which go beyond sentences like “I like this” and “I hate red”, and Bierut’s “design bullshit”. In a further section of the book, Shaughnessy gets closer to this picture, using the concept of “post-rationalization” instead of “bullshit”:

But I don’t think there’s necessarily anything wrong with it. The unconscious mind plays a part in the creative process – we don’t always know where ideas come from or why they appear, yet we know they are right. And since there are a few clients who find this sort of ‘unsupported’ creativity acceptable, we have to find ways of explaining it to them. After all, if it stands up to scrutiny, how wrong can it be?

That last sentence may well be the bridge between the subjectivity and objectivity strategies/theories in graphic design.