Freedom and Neurobiology

Review of Freedom and Neurobiology: Reflections on Free Will, Language, and Political Power by John R. Searle

Searle is always good at summarizing things, and the introduction entitled “Philosophy and the Basic Facts” offers a nice big-picture, including my favorite part of the book: a list of recent (last century) – and fortunate, in my opinion – changes in philosophy:

- Epistemology is no longer at the center of philosophy.

- Philosophy of language is no longer at the center of philosophy.

- Systematic large-scale philosophy is possible again.

- There is now no sharp distinction between philosophy and other disciplines.

The chapter on free will, however, doesn’t live up as we witness classic Searle reasoning through nothing but plain common sense and dismissing fruitful (and possibly accurate) ideas/theories on the basis that they are “intellectually very unsatisfying” (p. 62), or “literally incredible” (p. 77).

The most obvious and even fun case is on pages 45–46 where he literally uses his nemesis Dennett’s heterophenomenology approach (“Granted that we have the experience of freedom, is that experience valid or is it illusory?”), only to discard the illusion answer as it is “absolutely astounding”. One wonders how many more counter-intuitive facts we have to discover in order for him to abandon his intuitions; apparently the Copernican, Darwinian and Einsteinian revolutions weren’t enough.

In the end Searle declares that there are two viable answers to the question of free will: epiphenomenalism (i.e. free will in its ordinary sense is an illusion) and quantum indeterminism. For the latter, he bypasses the common criticism (“randomness isn’t freedom”) by proposing that randomness at the micro level may not necessarily imply randomness at the macro level. Yes, enter the almighty emergence…

For a book with a such promising title, it is disappointing to find out that the two chapters “Free Will as a Problem in Neurobiology” and “Social Ontology and Political Power” were written separately and only relate to each other as parts of a “much larger philosophical enterprise”. Nevertheless, the second chapter has proved useful to me with the concept of “desire-independent reasons for action”, getting close to answering a question pending in my mind for years: What motivates a rational person to vote in elections while she knows that her single vote isn’t going to change anything?

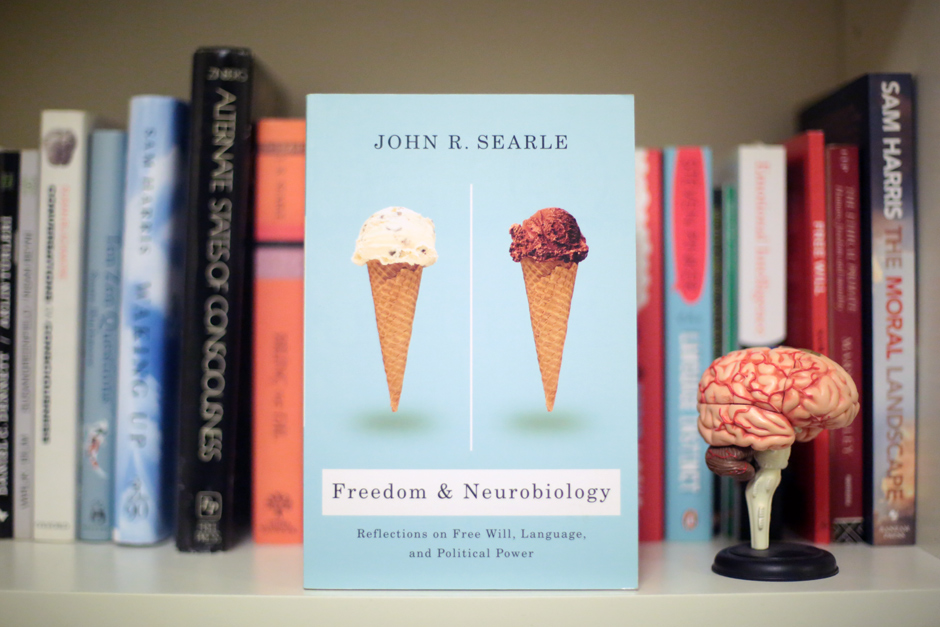

I must confess that, despite all its disappointments, I realize that I still like the book. I fear it may be because it has a marvelous cover.

Leave a Comment

Join the conversation.